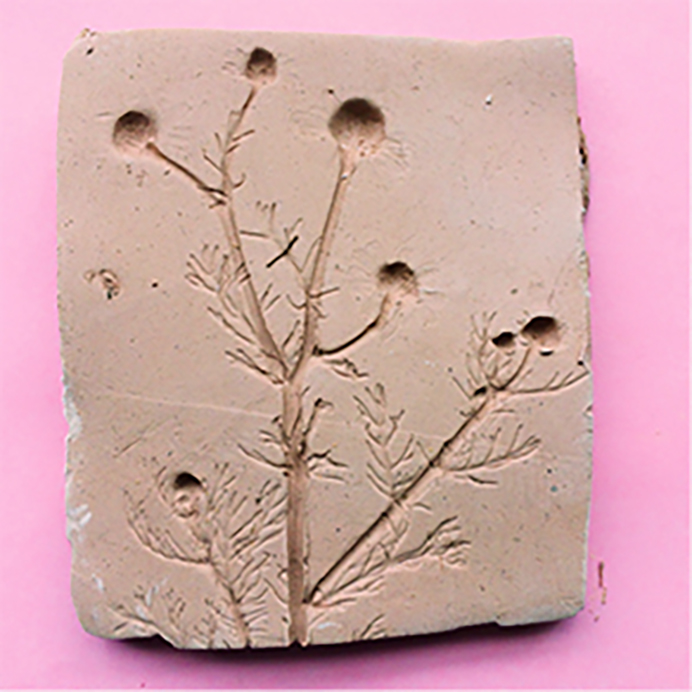

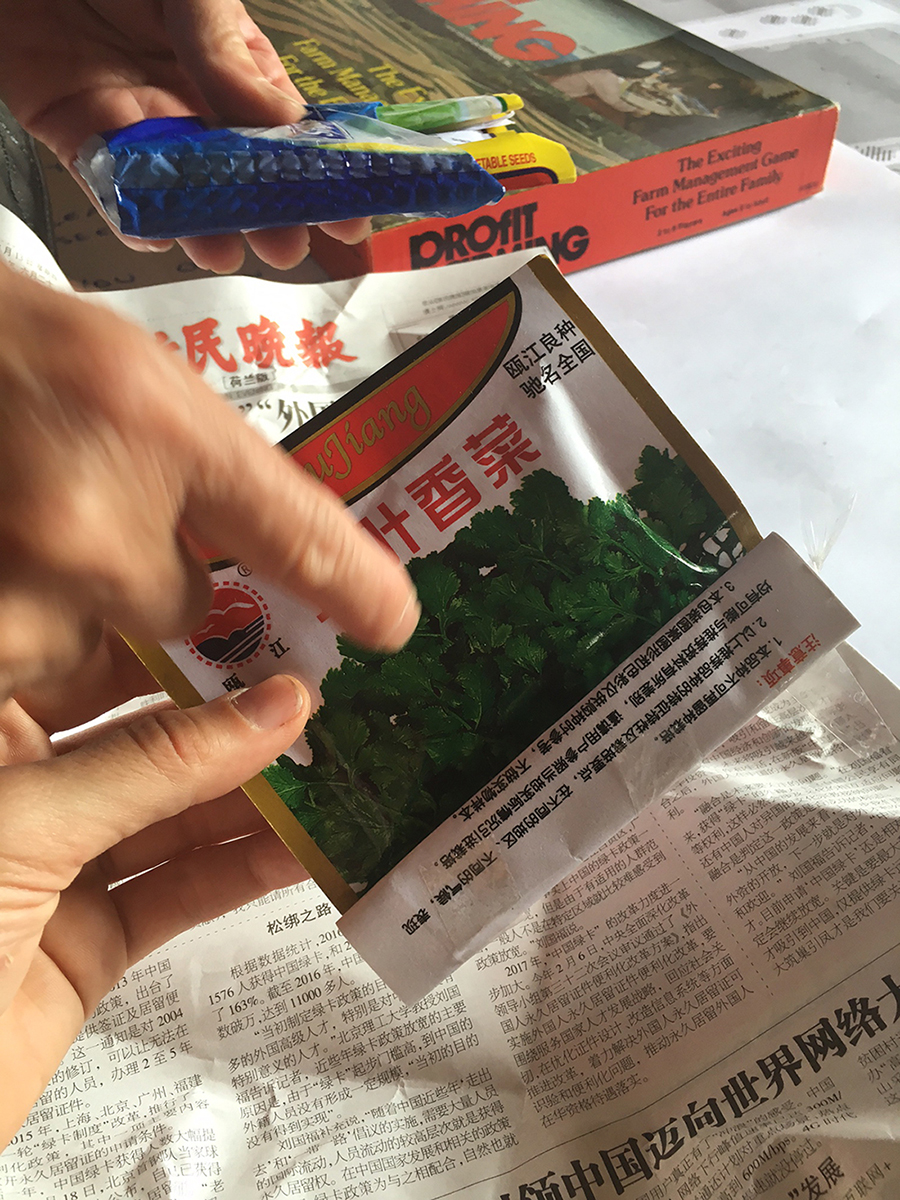

Fig. Soil exploring in Leidsche Rijn as part of Erfgoed (Agricultural Heritage and Land Use), 2018. Photo: Merel Zwarts

In the 1993 novel Parable of the Sower, Octavia Butler paints a picture of the United States in 2024; tormented by climate disaster, people live in gated communities where water and food are scarce and they protect themselves from the outside world with guns. Large-scale, drug-infused fires draw people out of their houses and onto roads which – they hope – lead to water, jobs and stability. The story sheds light on the increased isolation and aggression that humans find themselves in, both against each other and their natural surroundings: the destruction of the power of communality to make place for suspicion, fear, paranoia and individualism through an assertion of control over bodies, brains and places by means of a scarcity of resources. This ’93 vision of Butler does not seem too far off from our everyday reality, and indeed we can say that ‘our house is on fire’, and in fact has been for the last five-hundred+ years 1 a reality that comes with enclosures of collectively managed and maintained resources – commons, through colonization, privatization, extraction, and an upholding of class differences. As the protagonists in the novel do, some of us have been in search of other ways of living, working, or growing together.

Speaking from the field of art and organizational practice, everywhere around us we are in fact told we should be growing; a larger audience, more visibility, more program. Yet we should question what this call for growth means. The 2019 OECD report Beyond Growth: Towards a New Economic Approach argues for a redefinition of growth to ensure social wellbeing, cohesion and empowerment, and reflect the ecological limits of human activity. It questions how growth can be rethought as something sustainable, fair and collaborative, rather than extractive and competitive2. Whereas the notion of ‘degrowth’ is sought after in this light, at Casco Art Institute, a ‘still’ small art organization of on average six team members, we seek for this redefinition of growth and ask, how can ‘we’ grow together? Certainly we don’t want to go smaller in size, we would like to grow our collective power, we want to be more impactful in what we are doing, we individually all enjoy ‘growing’ in our maturity. It is not simply that we want to have a larger edifice, fundraise more to have more money, organize more public activities and enlarge the team. Nor that we want to make one show after another on degrowth, the counter narrative of economic growth and so on. Then how?

A key to this is considering relationships as a fundamental basis for the institution by understanding it as an ecosystem, beyond a team of waged workers, the board and a few representative artists and including practitioners of diverse backgrounds, other organizations and non-human beings. It means working and relating to each other becomes a fundamental part of institutional practice and listening becomes a key skill to cultivate.

Listening is a simple yet complex answer to the question of how to grow together. Listening signifies a movement between receiver and sender, when done right it is engaged, active and unconditional. But listening is hard. It is a practice that requires effort as we are untrained. It is counterintuitive: the feelings, emotions and anxiety that comes with an increased sense of competition ask of us that we overpower, enclose and exclude other institutions, practitioners or even (natural) forces as they pose a threat to our own practice, not hear and amplify what they have to say. But a skilled listener allows for relationships to shape and deepen by embracing what the other – in the broadest sense of the term, including nature, animals, objects – has to say, leading to mutual influence and interdependence. Taking this type of deep listening as a vantage point, we can reconceive our ways of individual growth to cultivate an art of growing together.

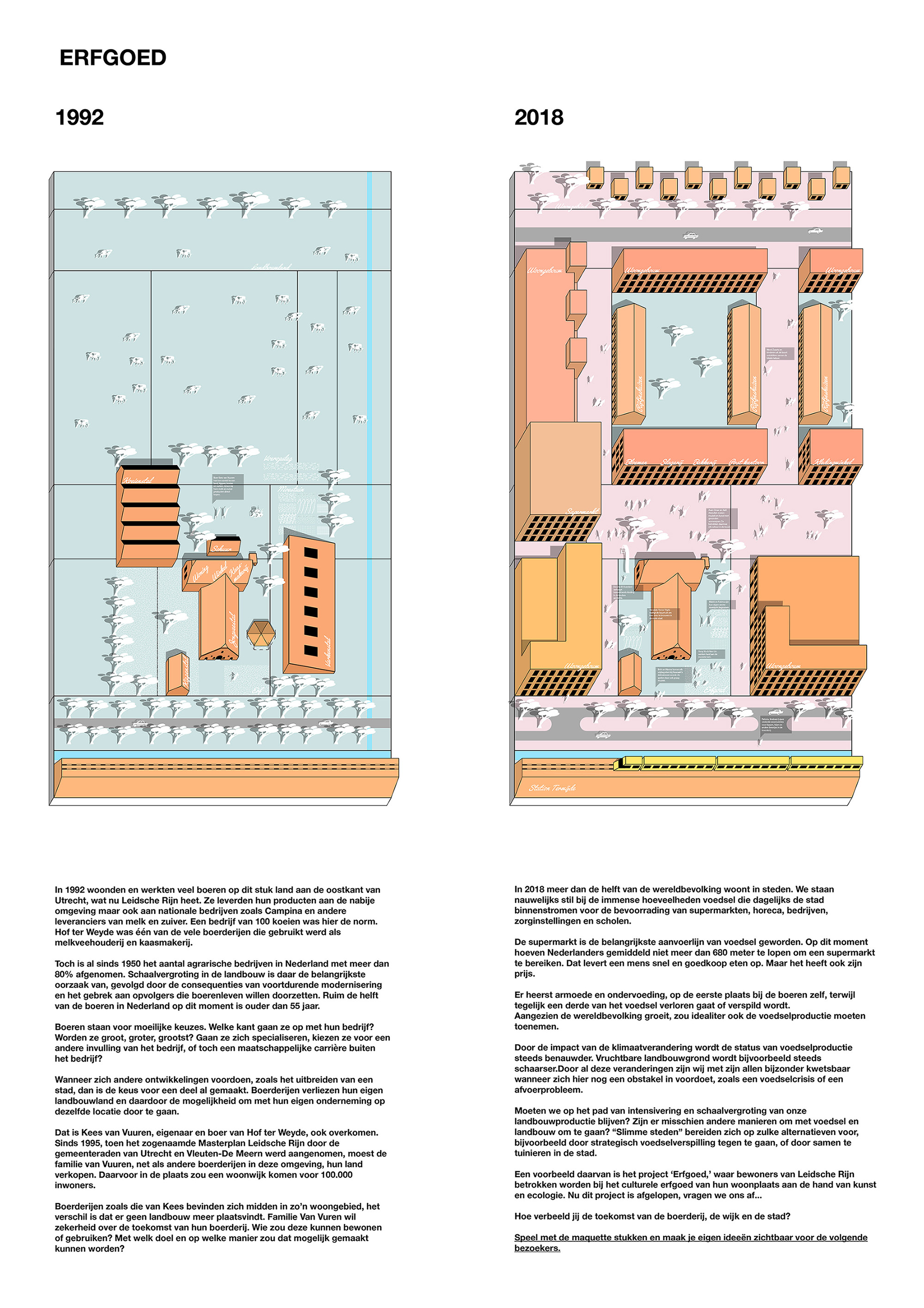

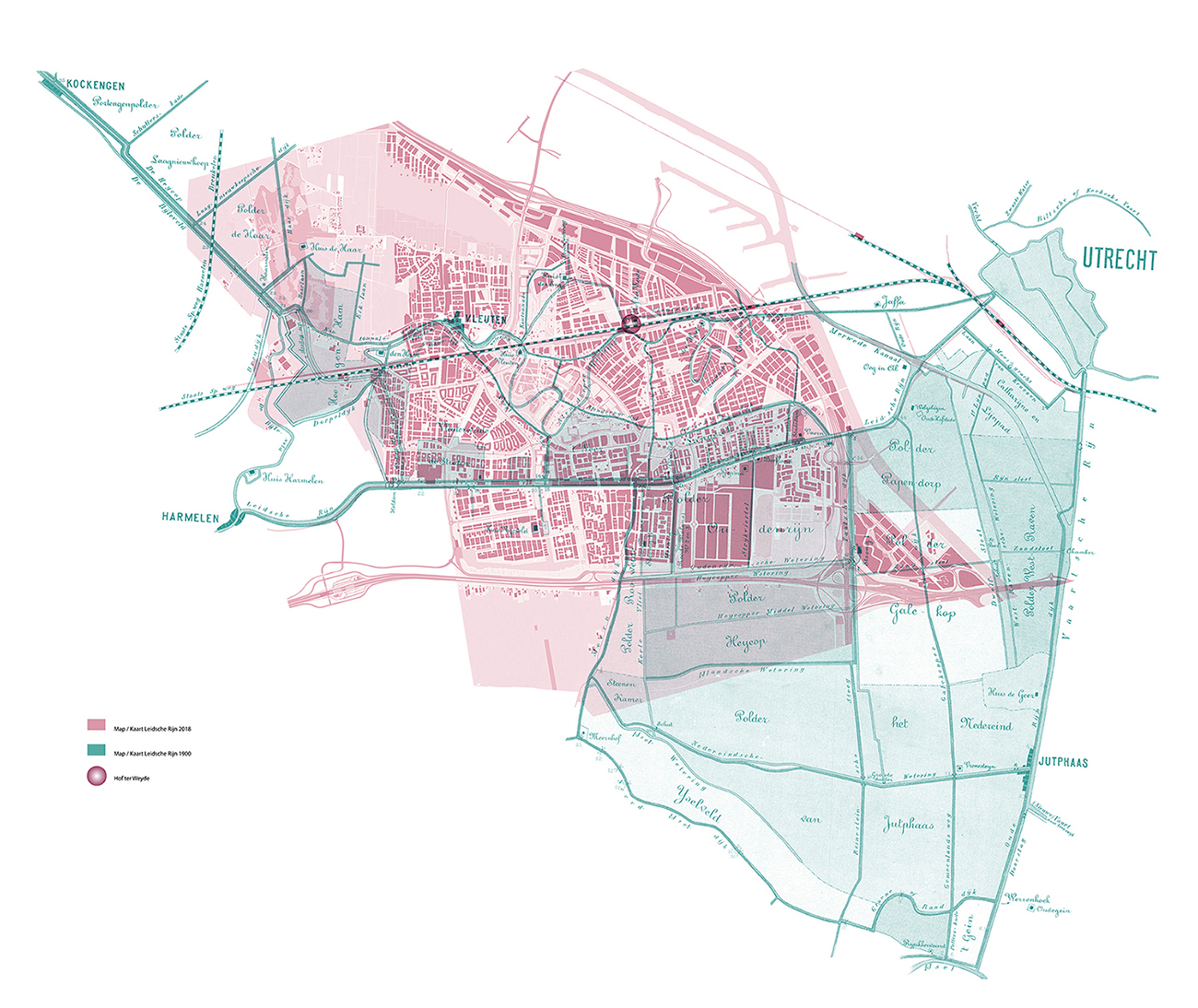

Artist duo Bik van der Pol, biotope for circular living Metaal Kathedraal and Casco Art Institute: Working for the Commons started listening to one another towards the end of 2019 with the aim of developing a new movement for sustainable, fair, mutual growth through a practice of listening and broadcasting. In doing this they have committed themselves to a place where they can work towards the development of common grounds; Leidsche Rijn, a new neighborhood in Utrecht built within the context of the so-called ‘vinex’ – a mandate released in 1991 that assigned larger outer city areas for housing development. They have also committed to one another in an effort to bring their practices, knowledge and skills together in a new initiative: the Leidsche Rijn Luister Academie (LRLA).

Before the developments started, Leidsche Rijn was a vast farmland, providing resources for the city of Utrecht and surrounding areas. The heritage of this place as farmland, the agricultural skills and relationships with the land have largely vanished as the developments progressed over the last 22 years. Confronted with a contemporary moment of ecological crisis, this site, as well as others find themselves at a pivotal moment: will they operate based on the premise of business-as-usual and become yet another sleepy suburb with a lack of site-sensitivity, or can the area reinvent itself to become a model and example for how we can and want to live together in the 21st century? It is this question that we bring to Leidsche Rijn Luister Academie (LRLA), one that commits the three parties to listening to the area of Leidsche Rijn as well as each other. The composition is unique: two artists, a visual arts institution and an ecological laboratory and platform. What binds all three is the ground itself: Leidsche Rijn, a place that connects each organization in its own way – to a mission of ecological development and bottom-up collaboration. Together they connect growth and listening in a small but precise ecosystem of three practices. LRLA provides a fertile ground for non-competitive, cooperative practices whereby institutions and individuals alike, of diverse backgrounds both human and non-human, become each other’s teachers, supporters and mentors for collective growth.

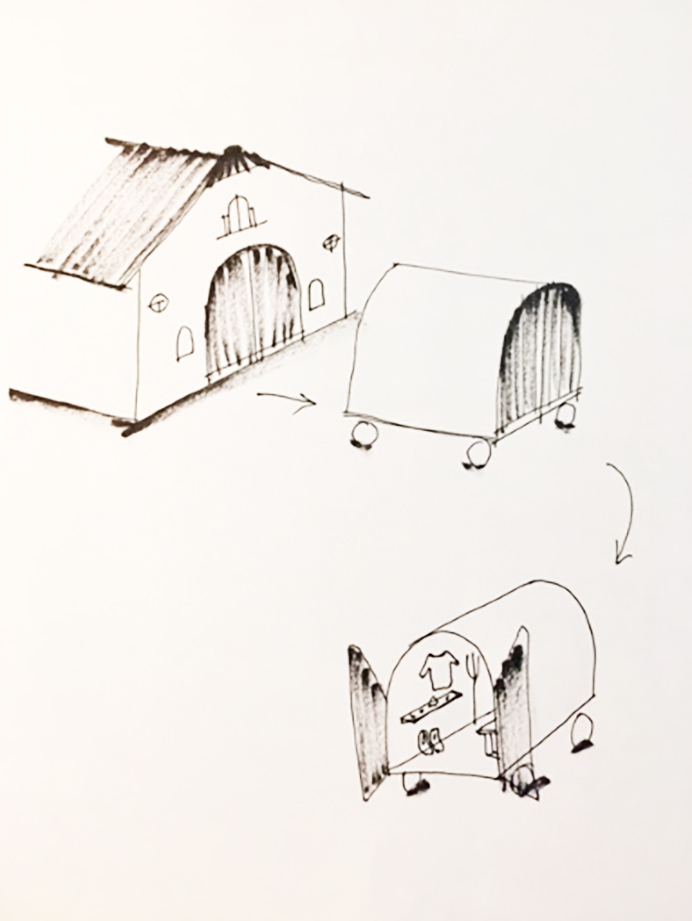

Fig. Listening to Leidsche Rijn with the Travelling Farm Museum of Forgotten Skills, 2020. Photo: Merel Zwarts

So what does this new way of growing together through a practice of listening look like? It is in the first place a site of development of skills in listening and broadcasting we have forgotten. Leidsche Rijn Luister Academie builds different, nomadic broadcasting stations and spaces for encounters as a way to listen to difference; the different programs, activities, publics and networks of the institutions and initiatives as well as the ecological and cultural diversity of Leidsche Rijn are brought together in mutual recognition that only grows in a sustainable way by recognizing they are all part of one ecosystem. This means in particular listening to those who are often ignored; children, those who don’t speak the local language, the land or what we would call ‘nature’ (soil, air, water, plants, insects and other animals and forms of life). A collectively developed and multiple-voiced infrastructure or platform shares skills, sounds, stories, voices and music that cultivate the skill of listening to each other – both human and non-human. This toolset must be built first, and offers a step in the direction of a collective program. To reverse this process would mean opening up to the risk of overshadowing one another’s program and identity in an exhausting process of negotiation where each party tries to demonstrate its originality and authorship. Such processes are competitive and lead to unproductive compromises and collaborations.

Butler writes that all struggles are essentially power struggles, and not at all refined, intellectual ones, but mere muscle competitions or ‘two rams knocking their heads together 3’. Instead of leaning into those struggles, what if we take a step back and look at our surroundings not as potential competitors but through a lens of communing practices as an institutional ecosystem, and by listening to each other build relationships based on mutualism where we exist, work and live together with our differences to amplify and broadcast all those things we hear from our surroundings and each other. This will not happen without building new skills and unlearning old habits, but it is a step towards a new way of coexisting outside of exploitation and competition. Instead we just listen.

1. In her 2019 World Economic Forum speech Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg exclaimed that ‘Our House is on Fire’ to which indigenous communities who are in constant struggle for their land and resources responded that in fact our house has been on fire for five-hundred years and it is only now that the West is waking up to this reality and acting upon it. The 2019 Assembly for commoning art institutions at Casco Art Institute took up this phrase as well as its implications to pose the question: What practical measures will art and art institutions take to care for our planetary commons with the power of imagination? Together with an editorial team with members from Code Rood, Platform BK, Commons Network, Fossil Free NL as well as individual artists, we developed a draft version of a climate justice code for art and art institutions which was collectively edited over the course of two days with a group of hundred Assembly participants.

2. Beyond Growth: Towards a New Economic Approach. Report of the Secretary General’s Advisory Group on a New Growth Narrative, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2019

3. Octavia Butler, Parable of the Sower. New York City (NY), Four Walls Eight Windows, 1993, p. 89

The never-ending story of commoning a farmhouse in the lost farmlands

Het oneindige verhaal over het commonen van een boerderij in een verloren landbouwgebied

Edited by Binna Choi, Asia Komarova & Rosa Paardenkooper

The never-ending story of commoning a farmhouse in the lost farmlands

Het oneindige verhaal over het commonen van een boerderij in een verloren landbouwgebied

Edited by Binna Choi, Asia Komarova & Rosa Paardenkooper